The 14-inch M1920 railway gun was built around a U.S. Navy-designed 14-inch/50 caliber gun. In fact, the gun barrel itself was the Navy’s Mark IV 14″ naval rifle. These were high-velocity naval guns (50 calibers long) originally intended for battleships, and several spares were available by the end of World War I. Rather than designing a completely new piece, the Army’s Ordnance Department adopted this Mark IV naval gun for coast artillery use, but re-designated it as the 14-inch Gun, Model of 1920 (M1920) when paired with the new carriage. In other words, the “M1920” designation refers to the Army’s adaptation of the Navy Mk IV gun for the 1920-era railway mount, not a different caliber or fundamentally new gun. Ballistically, the M1920 gun was the same 14″/50 (355.6 mm) firing the same 1,560 lb projectiles out to about 26–27 miles. Only four of these weapons were ultimately completed (two allocated to the Harbor Defenses of Los Angeles, and two to the Panama Canal Zone). Watervliet Arsenal manufactured the 14″ guns for this project in the mid-1920s, using the Mk IV naval design as the basis. By 1925 the first units were ready for testing, and they entered service a few years later (the Army records list them as Gun, 14-inch, M1920 with individual serial numbers)

Mk IV vs. M1920 – what’s in a name? It’s important to clarify the nomenclature: “Mk IV” was the Navy’s mark number for the gun barrel design, whereas “M1920” was the Army’s model/year designation for the gun once adapted. Technically, they refer to the same 14-inch gun, but in Army service the piece was simply called 14″ Gun M1920. In fact, Army supply catalogs list the weapon as “Gun, 14-inch, M1920MII … (Mk. IV Mod 1 and M1920MI) on Railway Mount M1920”, indicating the Navy Mark IV lineage. The Army-built guns underwent minor modifications: the Navy’s breech mechanism was adjusted for the new mount. Early barrels (M1920M I) had the breech block’s axis rotated 16° counter-clockwise to clear the recoil cylinders (“recoil band”). Later ones (M1920M II) used a straight-aligned breech, simplifying the design. These tweaks aside, a 14″ M1920 gun was, at its core, a 14″/50 Mk IV naval rifle fitted for Army use.

The Model 1920 Railway Carriage

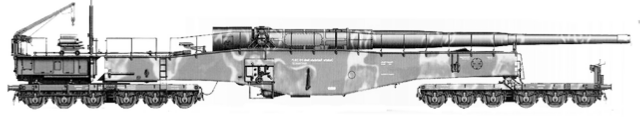

The railway mount that carried the 14″ gun was officially the 14-inch Railway Carriage, Model of 1920 (often shortened to “M1920 carriage”). This was a new design developed after WWI, incorporating lessons learned from earlier railway artillery. The M1920 carriage was indeed unique – it was not the same as the Navy’s WWI-era mounts. The carriage had an enormous 14-axle railroad chassis (8-wheel bogie in front, 6-wheel bogie in rear) to distribute the 365-ton weight of gun and mount on the rails. For transport, the gun sat on this rolling stock, but the key feature of the M1920 carriage was its ability to transform into a fixed firing platform.

Unlike the WWI designs, the Model 1920 mount could be raised or lowered by built-in jacks. At a prepared firing site, the crew would jack the carriage up, remove the bogies (“trucks”) from under it, and lower the entire gun mount onto a steel center pivot set in a concrete pad. Once bolted down to this pivot, the gun had a stable, absolutely level platform allowing full 360° traverse for tracking targets (a crucial advantage against moving ships). In effect, the M1920 carriage could function as a permanent coast artillery barbette emplacement when emplaced, yet it retained mobility – truly a “universal” mount. An Army journal in 1922 described it as “a coast-defense weapon that is more universal in type than any that have gone before”, noting that it combined high mobility with the essentials of a fixed seacoast battery. When locked into its firing platform, the mount provided a level turntable so the gun could traverse without needing to re-level for each shot. Power traverse and elevation motors (fed by an onboard generator car) allowed the crew to swing and aim the heavy gun relatively quickly by mechanical means(manual cranks were also provided as backup). The carriage’s elevation mechanism allowed the gun to be fired at high angles (up to ~50°) to reach maximum range, all without needing a deep recoil pit under the tracks as earlier models did.

In railway mounted mode, the M1920 gun sat centered on the railway car and could fire in a limited arc using the tracks for azimuth. With the bogies attached and the gun locked in its traveling position, it had about 7° of traverse on the rails (by pivoting slightly on curved track segments)– enough for rough aiming or emergency use. Standard procedure was to lay a curved section of track (“crossing the epaulement”) to give additional traverse when firing from rails, but for full coverage the preferred method was to emplace on the pivot. The design also allowed firing from improvised field positions if needed: the Army noted the mount “may be used on a temporary field emplacement, thus supplying the need for a mobile weapon of extreme range” in land warfare. In practice, the four M1920 guns were deployed as coast defense weapons: two defended Los Angeles harbor (Battery Erwin at Fort MacArthur) and two were sent to the Panama Canal, where they could be moved by rail between Pacific and Atlantic sectors.

Evolution from Earlier Models (Mk I, Mk II to M1920)

The 14″ M1920 system was a direct outgrowth of the U.S. experience with heavy railway guns in World War I. During the war, the Navy had built the first 14″ railway batteries using the same Mk IV guns on simpler rail mounts:

- Mk I Naval Railway Mount (1918): The initial design built by Baldwin for the Navy in WWI. Five of these were sent to France in 1918. The Mk I mount was essentially a big steel railroad car with an armored gunhouse. It had two 6-wheel trucks (12 axles total) and used a top-carriage recoil into a pit: for high elevations, a 9-ft deep pit had to be dug under the track to accommodate the gun’s recoil and breech drop. Traverse was achieved by laying curved track segments – the mount itself had no built-in traversing mechanism beyond what the rails provided. This meant repositioning the entire car for aiming, a slow process. The Mk I could elevate to ~43°, but above 15° the recoil pit was mandatory. These Navy-operated batteries proved effective in France, but their fixed firing procedure (digging pits, etc.) was laborious.

- Army Mk I Mounts (1918): The Army ordered six mounts similar to the Navy’s Mk I in 1918 (intending to field its own railway artillery). All were finished by late 1918, but none reached France before the Armistice. These presumably would have used the same Navy Mk IV guns. They remained stateside and gave the Army a starting point for postwar improvements.

- Mk II Naval Railway Mount (1919): As the war was ending, the Navy developed an improved mount addressing the Mk I’s shortcomings. The Mk II mount (two built by 1919) still carried a 14″/50 Mk IV gun, but dispensed with the gun shield and recoil pit altogether. Instead, it adopted the French-style rolling recoil: after firing, the entire railcar would roll backward 30–40 ft to absorb recoil, enabled by inclined rails and robust anchoring. The gun sat higher on the carriage so it wouldn’t hit the ground at maximum elevation, and the weight was spread over 20 axles to reduce ground pressure. This meant the Mk II could fire at any angle up to ~40° without any excavation, a huge improvement in speed of operation. The tradeoff: like the French rail guns, it still relied on a curved track for major azimuth changes and had to be hauled back into position after each shot (which was done with a winch). The war ended before the Mk II saw combat, but these mounts were retained for U.S. coast defense use in the early 1920s.

From Mk II to M1920: The Army’s Model 1920 railway gun took the next step in this evolution. After WWI, the Coast Artillery Corps and Ordnance Dept wanted a railway mount that could engage enemy vessels over a wide sector, not just along a fixed track line. The solution was to combine mobility with a pivoting base. Essentially, the M1920 design added a center pivot and jacking system to what was learned from the Mk II. This gave the best of both worlds: the Army’s new 14″ mount could be transported wherever needed by rail, yet at a prepared firing point it became a fully traversing fixed battery. A 1922 Ordnance report highlighted several unique features of the M1920 carriage: no recoil pit or complex emplacement required (just a flat concrete ring), ability to use either fixed magazines or ammunition cars for supply, and even the ability to fire from a “temporary field emplacement” if necessary. In short, the 14″ M1920 system was far more “universal” than earlier heavy artillery: it was mobile, had all-around fire, high elevation, and could be power-operated, something no previous single design had achieved

Gun/Carriage Pairing and Technical Distinctions

What made the M1920 gun & carriage pairing unique was this marriage of a proven naval gun with an innovative mount:

- Gun (14″ Mk IV vs M1920): The Navy’s Mk IV 14″/50 guns gave the Army a ready heavy weapon without new development. The Army’s “Model 1920” guns were essentially those barrels adapted for the new mount. The differences were administrative and minor mechanically – e.g. slight breech block reorientation as noted above– rather than any difference in caliber or performance. In fact, one of the Navy-built Mk IV guns on a WWI-era carriage survives on display (at the Washington Navy Yard), illustrating that the same basic gun served in both WWI and the M1920 systems. The Army Ordnance Technical Manuals of the 1940s (for example, Field Manual FM 4-35, “Service of the Piece – 14-inch Gun M1920MII on Railway Mount M1920”) used that nomenclature, confirming that the official pairing was the “14-inch Gun, M1920, on Railway Mount M1920.”. The M1920 gun could be called a direct “upgrade” of the Navy’s weapon – it remained a 50-caliber rifle but optimized for coast defense use.

- Carriage (earlier vs M1920): Compared to earlier 14″ railway carriages (Mk I and Mk II), the M1920 had far more capability for traverse and emplacement. The pivot-jack system was entirely new. Earlier mounts required the railway tracks themselves to provide azimuth (by building curved spurs or traversing on a segment of track). The M1920 carriage still allowed on-track firing in a pinch, but its design acknowledged that truly tracking a moving ship demanded a fixed pivot. Thus, permanent concrete rings were built at its assigned defense sites; the carriage would be lowered onto these for action. Once on the pivot, the gun could slew 360° (something impossible for any previous railway gun without literally building a full circle of track). Additionally, the M1920 mount included integrated elevation and traversing machinery powered by an electric generator, whereas earlier mounts were largely hand-worked or had very limited powered systems. The stability of the platform was also greater – by dropping the car onto a firm base, the M1920 avoided the inherent wobble of a rail car. Contemporaries noted that “the concrete emplacement is of very simple form and requires no pit”, avoiding problems of water table or construction difficulty near the shore. This was a clear improvement over the Mk I’s pit and even over some fixed gun emplacements of the day.

In Summary

The 14-inch M1920 railway gun consisted of a Navy Mk IV 14″/50 gun (redesignated as Model 1920) mounted on a Model 1920 railway carriage. The combination was the last and most advanced heavy railway artillery system deployed by the United States. It evolved from the WWI-era designs by adding the crucial ability to operate either as a mobile railroad gun or as a fixed coastal battery, with rapid conversion between the two modes. The M1920’s gun remained the same powerful 14″ naval rifle used in WWI, but its carriage was entirely new, allowing the weapon to cover wide arcs and engage targets with a flexibility not seen in earlier models. This unique gun/carriage pairing was documented in detail by the Ordnance Department in the early 1920sand in War Department manuals through the 1940s, solidifying its identity as “14-inch Gun M1920 on Railway Mount M1920.”

Sources:

- U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command – Historical Summary of the U.S. Naval Railway Batteries in WWI (mentions use of 14″/50 Mark IV naval rifles).

- Army Supply Catalog (SNL E-9) – lists “Gun, 14-inch, M1920… (Mk.IV)… on Railway Mount M1920”, confirming gun/mount designations.

- Fort MacArthur Museum archives – details on 14″ M1920 guns #7 and #10 on Model 1920 MII carriages, built by Watervliet (1938 report).

- Army and Navy Register, 14 Oct 1922 (cited in USNI Proceedings) – description of Model 1920 railway mount debut, highlighting its 360° traverse, no-pit emplacement, and “universal” coast-defense features.

- Wikipedia/Military archives – “14-inch/50 caliber railway gun” (WWI service of Mk IV guns) and “14-inch M1920 railway gun” (overview of M1920 system and breech modifications). These summarize technical details drawn from U.S. Ordnance Corps references and Mark A. Berhow’s American Seacoast Defenses.