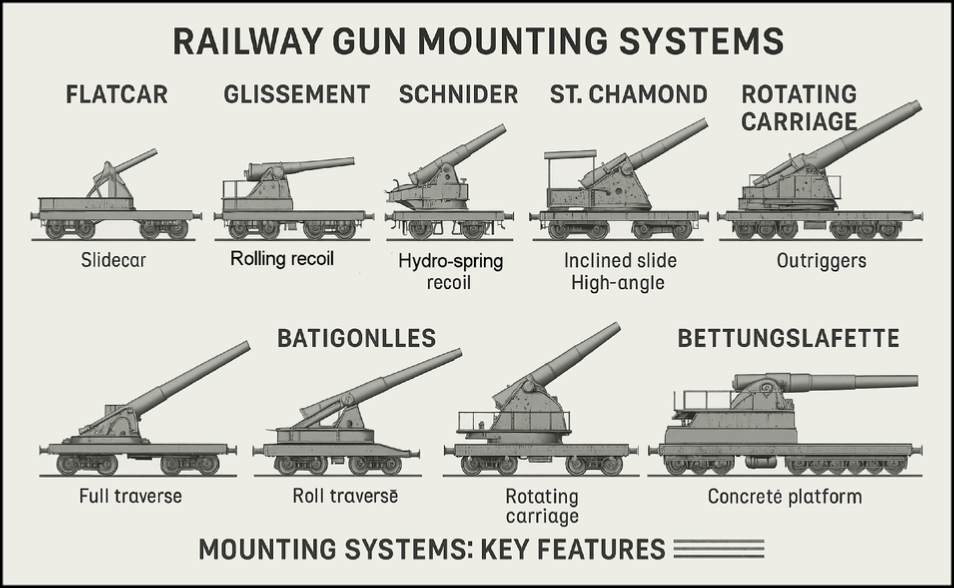

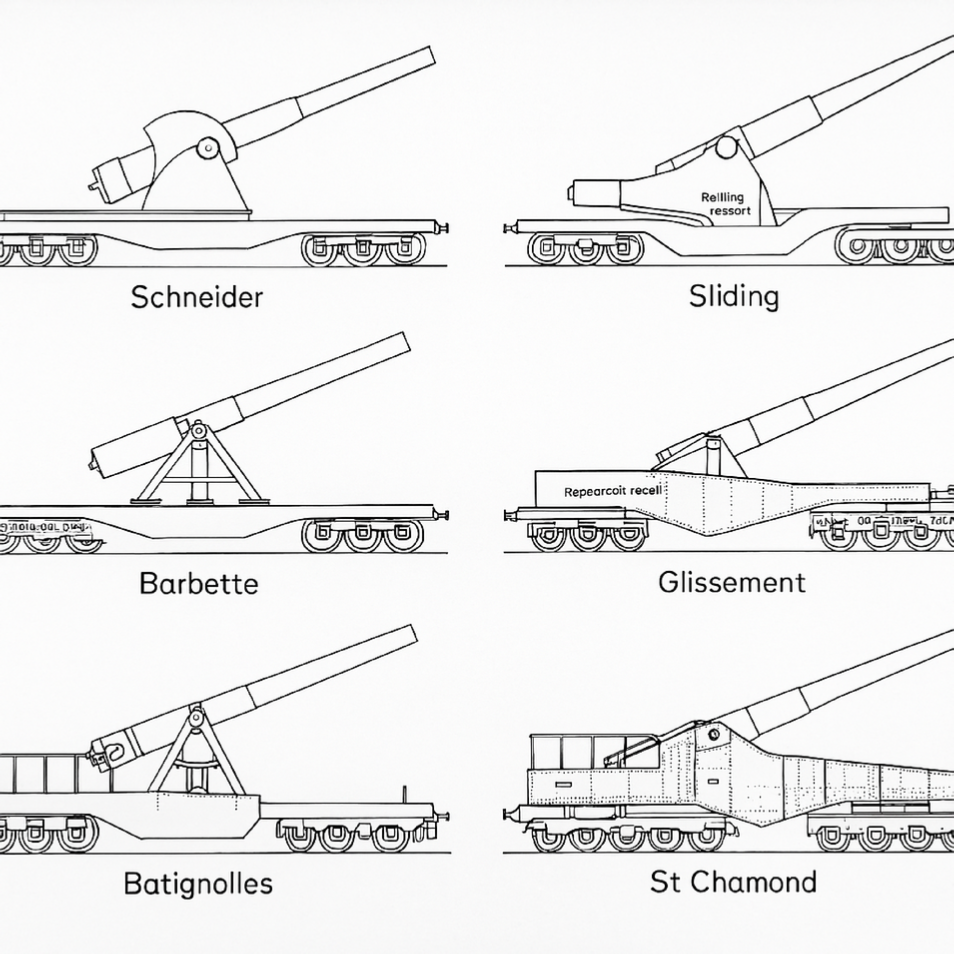

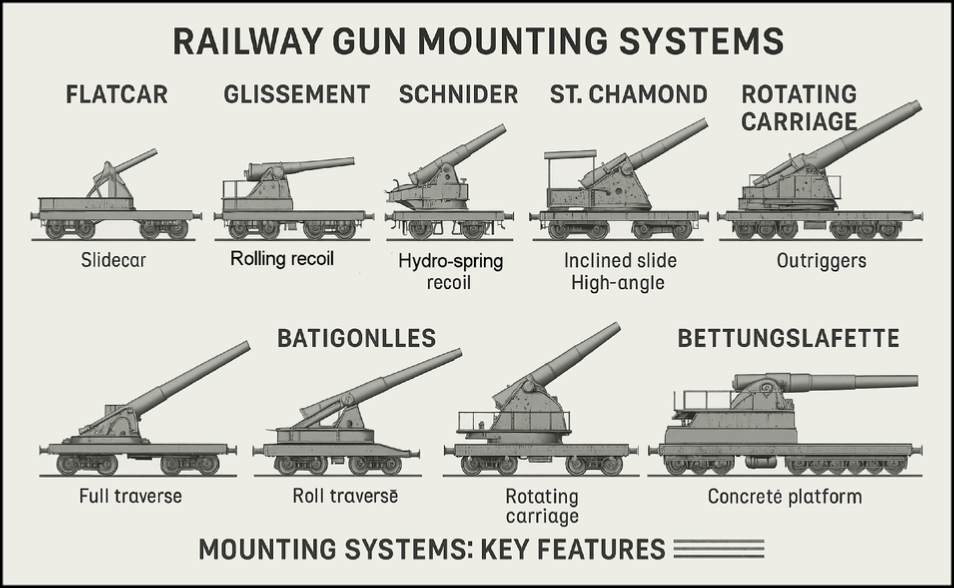

Guide List of Major Railway Gun Mounting Systems

(U.S. Civil War – WWII Railroad Guns)

Railway artillery evolved a variety of mounting systems to handle massive guns on rails. Below we detail the key mount types used by the U.S., France, Britain, Germany, and others from the American Civil War through World War II. For each, we outline the design, nations of use, technical features (recoil, traverse, stabilization), visual identifiers, notable examples, and pros/cons.

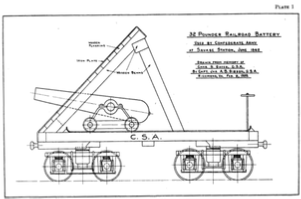

Early Flatcar and Pivot Mounts (19th Century)

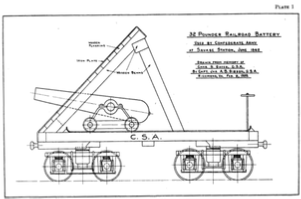

In the U.S. Civil War, the first railway guns were field or naval cannons simply bolted onto flatcars or swiveling pintle mounts. The Union’s “Dictator” mortar and Confederate Brooke rifles were placed on reinforced flatbed railcars.

- Nations: United States (Civil War), later adopted in concept by others for improvised use.

- Design: Essentially a flatcar with a gun on a fixed or limited-traverse pivot. No special recoil system – recoil was absorbed by the car’s weight or by rolling slightly on the rails.

- Traverse: Very limited (often the entire car had to be angled on curved track or moved for aiming).

- Stabilization: Minimal – crews might chock wheels or reinforce the car. Visual ID: Looks like a standard rail wagon with a gun mount on top; often an open wooden or steel flatcar.

- Notable Examples: The 32-pounder Brooke rifle mounted by Confederates at Savage’s Station; the Union’s 13-inch siege mortar “Dictator.”

Pros and Cons:

- Pro: Quick and simple way to mobilize heavy guns (pioneering the concept of railway artillery).

- Con: Crude aiming and poor recoil control – after firing, such cars often rolled back or required re-aiming. These mounts set the stage for more sophisticated designs as heavier guns came into play.

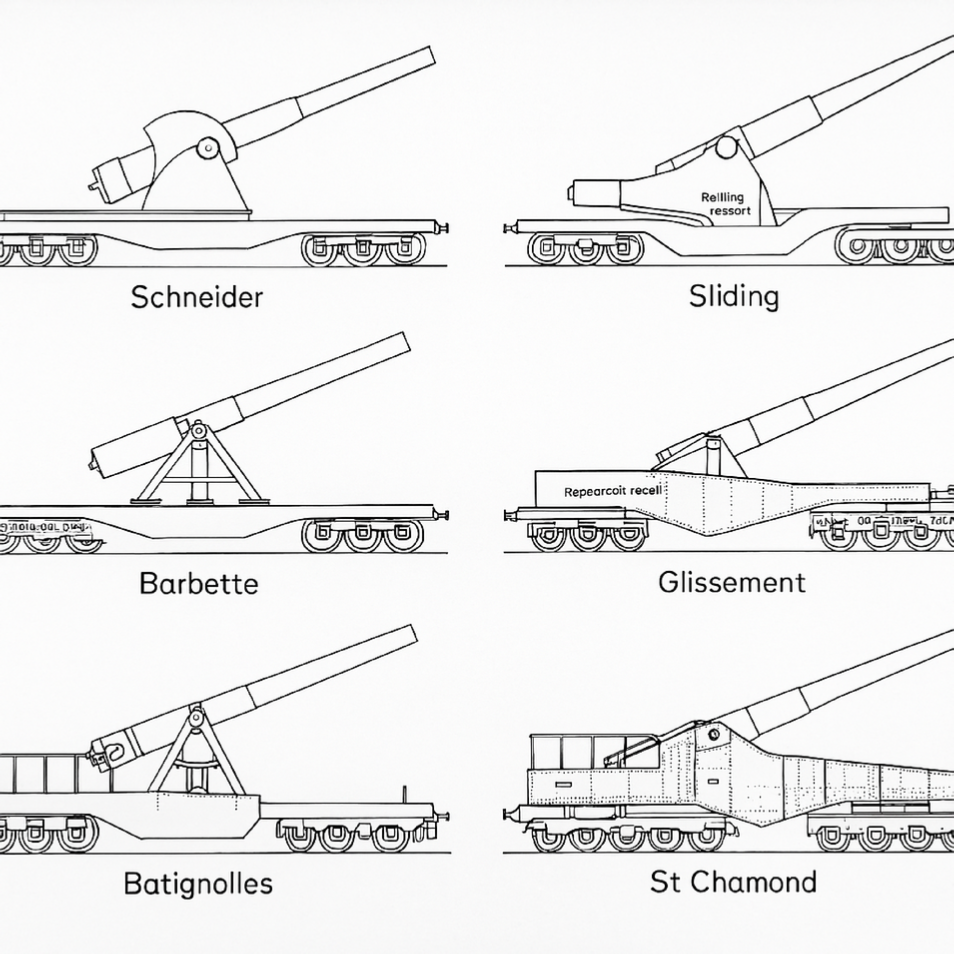

Schneider Cradle Mounts (Top-Carriage Mounts)

By World War I, France’s Schneider company designed more advanced railway carriages using a top-carriage (cradle) recoil system with the gun mounted on a robust steel frame.

- Nations: France (Schneider et Cie.), Britain (similar concept on some 9.2-inch and 12-inch guns), U.S. (adapted for some post-WWI designs).

- Design: A hydro-pneumatic or hydro-spring recoil cradle holds the gun; when fired, the gun recoils in this cradle like on field artillery. The carriage is anchored to the rails via clamps, jacks, or struts instead of rolling back. Recoil force is absorbed by the gun’s internal recoil mechanism and transmitted down into the track. Often called “affût-truck” in French service.

- Traverse: Usually limited to a few degrees on the mount (for fine adjustment). Major azimuth aiming required the entire carriage to be aligned (e.g. using curved track segments or switches).

- Stabilization: Typically rail clamps or screw jacks were employed to secure the carriage to the tracks when firing. Some models had drop-down outriggers or struts to the ground for stabilization. No large prepared platform was needed – the railway track itself (if well reinforced) took the load.

- Visual ID: Schneider-type mounts often featured a long girder-style railcar frame with multiple axles (e.g. two 4-axle bogies), a central recoil cradle with large hydraulic cylinders visible, and sometimes a small gun shield. They lacked the elaborate firing platforms of other types. When in firing position, one may see clamps on the rails or deployed jacks.

- Notable Examples: French 194mm and 240mm guns Mle 1870/93 on Schneider carriages (these used rail clamps/guys for anchoring). The French 155mm GPF gun was also adapted to a Schneider-designed rail mount. The British 9.2-inch railway guns and 12-inch howitzers similarly used on-carriage recoil with rail clamps.

Batignolles Ground Platform Mounts (Berceau System)

French manufacturer Batignolles developed a sophisticated mounting that combined a top-cradle recoil system with a demountable firing platform for heavy guns. Often called affût à berceau (“cradle mount”), these are characterized by the gun being placed on a central pivot on a prepared platform, allowing wider traverse.

- Nations: France (Batignolles), United States (license-built for 12-inch M1895 guns), Great Britain (similar “ground platform” mounts for 12-inch howitzers), Germany (comparable use of Bettung platforms).

- Design: Upon reaching the firing site, the rail car would be anchored to a pre-built steel and timber platform that transferred recoil to the ground rather than the rails. Typically, several steel cross-ties with integral spades were driven between railroad ties, and heavy girders were laid across to form a stable base. The carriage was then bolted to this platform (effectively off-loading it from the rail wheels). The gun itself had a hydro-pneumatic recoil cradle (“berceau”) to absorb recoil in elevation, while the platform absorbed horizontal forces. A recoil pit was usually dug under the breech to allow high elevation recoil clearance.

- Traverse: Once on the central pivot of the platform, these mounts could achieve up to 360° traverse (full circle) if unobstructed. In practice, heavy outriggers or the platform ring allowed broad traverse (often 120°–360°). Some models also had “car-traverse” – the ability to shift the entire car a few degrees on its bogies for fine lay without unbolting.

- Stabilization: Very high – the permanent or semi-permanent emplacements bore the recoil. The process of assembly took a few hours (digging the pit, bolting down beams), but afterward the gun was extremely stable.

- Visual ID: Batignolles mounts in firing position will have jacked-down supports and beams under the carriage, sometimes almost appearing as if the gun is sitting on the ground. The rail wheels may be lifted off the track. Often a circular base or pivot is visible beneath the carriage. These mounts are large and heavy – e.g. French 370 mm howitzers on Batignolles mounts had five cross-ties and 12 anchor flanges on the carriage. In travel mode, they look like massive railcars with perhaps outriggers folded alongside.

- Notable Examples: The French 370 mm Howitzer Mle 1915 on Batignolles mount – eight built, each requiring a prepared firing platform. The Canon de 305 mm Mle 1893/96 à berceau (12″ gun) – Batignolles built 8; these also used anchored platforms and had limited onboard traverse. The U.S. 12-inch M1895 guns were mounted on the M1918 railway carriage, a direct copy of the Batignolles cradle system (license obtained in WWI). U.S. examples (though completed too late for WWI) could rotate 360° when emplaced and were used in coast defense.

Pros and Cons

- Pros: Allowed very heavy guns to be traversed and elevated freely, essentially acting like a fixed artillery battery that could still be moved by rail. The recoil was well-managed by the platform, enabling use of the largest calibers (French 340 mm, 370 mm, even 520 mm howitzers).

- Cons: Slow to deploy – building the platform and pit often took several hours or more, reducing mobility and making them vulnerable if relocation was needed quickly. The mounts themselves were enormous and complex, requiring cranes and supply trains. However, in static battles (e.g. trench warfare or coastal defense) this trade-off was acceptable.

A U.S. 10-inch railway gun on a Batignolles-style mount (M1918 carriage) at Camp Eustis, 1921. Note the massive 12-axle carriage and the pivot mechanism (hidden under the carriage) which, when emplaced on a prepared platform, allowed full 360° traverse. The large detachable side brackets and anchored beams (not attached in this travel configuration) were used to secure it during firing

“Glissement” Sliding Mounts (Rolling Recoil Carriages)

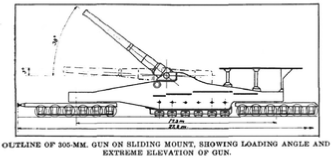

Introduced by the French in WWI, à glissement (sliding) mounts allowed the entire gun carriage to roll freely along the rails to absorb recoil.

- Nations: France (notably Schneider/Creusot and St. Chamond designs), United States (built one copy), Britain (some early experiments), Italy (limited use).

- Design: No traditional recoil mechanism – the wheels were left unbraked so the gun car would recoil along the track when fired. After firing, the carriage could roll back several meters, then was winched or pushed forward to firing position again. Often a track-mounted buffer stop or earth embankment was placed behind to arrest recoil.

- Traverse: Essentially zero on the carriage – aiming had to be done entirely by curving the track or positioning the entire gun toward the target. (Some sliding mounts had tiny adjustments by pivoting trucks, but effectively no onboard traverse).

- Stabilization: Minimal preparation – crews ensured a straight, level piece of track; in some cases sleepers (ties) were reinforced and structural beams (“jack sleepers”) laid under the rails to support the weight. Before firing, the carriage was usually not even clamped (to allow it to roll), though brakes could be engaged at the end of recoil.

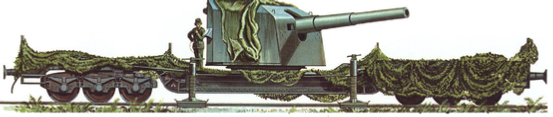

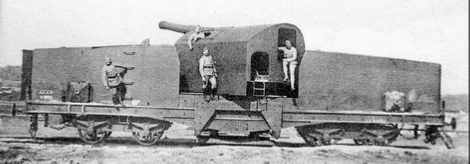

- Visual ID: Sliding mounts often had a very long recoil distance evident between the end-of-track buffers and the firing position. The carriages were relatively simple, sometimes with a rectangular steel girder frame. One distinctive French example had a boxy armored housing around the breech. You might see a recoil pit or ramp behind the car where the carriage would roll into.

- Notable Examples: The French 305mm Canon de 305 modèle 1893/96 à glissement (Schneider built 8 for France) – when fired, the entire 10-inch gun and carriage rolled back ~1 meter. The Canon de 340 modèle 1912 also used a sliding mount. The U.S. built one copy (the “Model 1919” 10-inch sliding mount) at Watertown Arsenal.

Pros and Cons

- Pro: Simplified engineering – no complex recoil cylinders needed, which sped up conversion of naval guns to rail use early in the war.

- Con: Absolutely required special track arrangements to aim and absorb recoil. Rate of fire was slow, as repositioning the carriage after each shot took time. Inability to traverse was a tactical limitation. Nonetheless, sliding mounts were crucial stop-gaps early in WWI when heavy guns were urgently mounted on railcars.

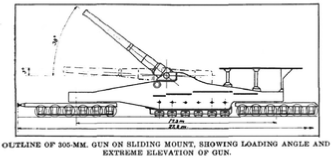

Diagram – French 305 mm gun on a sliding mount, showing how the entire carriage rolls back on rails to absorb recoil. These mounts had no built-in traverse, so track curvature was used for aiming. The gun is shown at loading angle (depressed) and at high elevation.

Pros and Cons

- Pro: Faster to deploy than those requiring a prepared foundation – just roll the gun into position and clamp it down. The self-contained recoil system reduced stress on tracks.

- Con: Limited traverse meant the tracks had to be pointed roughly on target. Also, very heavy recoil still imposed strain on rail ties, so extensive track bracing was often needed. Overall, Schneider mounts were robust and efficient for medium-caliber guns, and their simplicity made them popular. (Note: Schneider also pioneered fully rotating mounts – see “Chilean-type” below.)

Creusot “Chilean” Rotating Mounts (Fully Traversing Carriages)

In some cases, Schneider-Creusot (France) combined the mobility of a railcar with an integrated rotating platform. A notable example is a type of mount originally built for Chile’s coastal defense guns around WWI, which we’ll call the “Chilean-type” mount.

- Nations: France (Schneider/Le Creusot works), Chile (intended), United States (adopted design for 8″ and 12″ guns post-WWI), Britain (some comparable rotating mounts for 12″ guns by Armstrong).

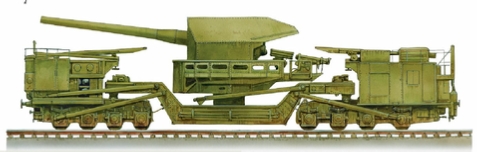

- Design: This mount featured a turntable or pivot built into the railcar itself. In effect, the carriage carried a circular ring rail and roller bearing on which the gun’s chassis could rotate. In firing position, the carriage would be jacked up off its bogies and the whole top portion could slew around. Some designs had an armored turret-like housing for the gun breech. For example, Schneider’s 194 mm gun mount of 1914 had a steel frame that rotated on rollers over a cast-steel base, with a ring gear for traverse. These mounts often included outriggers or jacks that dropped to support the car during firing and to level it when rotating.

- Traverse: All-around traverse (360°) when properly emplaced. Unlike Batignolles mounts which required assembling a platform, the Chilean-type mounts had the rotating platform built-in, so once jacked and secured, the gun could be slewed quickly to any azimuth.

- Recoil: Typically handled by a top-carriage hydro-pneumatic system (the gun recoiled in its cradle) plus any remaining force transmitted through the car’s jacks. These did not recoil along the track.

- Stabilization: High – to fire broadside, they relied on heavy jacks and sometimes folding supports. For instance, U.S. designs had outriggers that folded out and jacked down to the ground to take the weight off the trucks. This effectively planted the mount firmly.

- Visual ID: These can resemble a mix between a railcar and a seacoast turret. Look for a cylindrical or polygonal turret or shield on the car, and often a built-in circular track or geared ring at the car’s base. For example, Schneider’s prototype 194 mm Chilean mount had a prominent armored gun house and a boom crane on the car for ammunition. American versions (like the 8-inch M1888 on M1918M1 carriage) had a distinctive central pivot and outriggers (the 8″ M1918 could rotate a full 360° when its outriggers were deployed).

- Notable Examples: The Chilean contract 12-inch guns (Bethlehem-built) – by 1918, Schneider had designed a rotating mount for six 12″/50 guns ordered by Chile. Three mountings were finished by the Armistice, but they were never delivered due to the war’s end. The design was adopted by the U.S. Army for its own railway artillery: after WWI the U.S. built a common carriage for 7″, 8″ guns and 12″ mortars with outriggers and a pivot allowing all-around fire. These became the 8-inch M1918 and related mounts, used through WWII for coastal defense – they could be fired either from a curved track (up to ~7° traverse on rails) or placed on a fixed pivot base for full rotation. The 14-inch M1920 gun carriage is another example: it could be lowered onto a fixed pivot point at prepared firing sites, enabling rapid 360° traverse to track moving naval targets. (When not on the pivot, it had a limited 7° traverse on track

Pros and Cons

- Pros: Merges mobility with true all-around aiming capability – essentially a “mobile turret”. In coast defense drills, U.S. railway guns on these mounts could be unlimbered and firing in under 30 minutes, engaging targets anywhere on the horizon.

- Cons: Complexity and weight – these mounts were very heavy and expensive. The built-in turntable added height and required powerful jacks. They were also relatively few in number due to cost.

Overall, the Chilean-type/rotating mounts represent the pinnacle of railway gun mount evolution – the U.S. 14″ M1920 was the final heavy railway gun deployed by the Army, incorporating lessons to allow both rolling fire and fixed pivot fire.

Barbette and Fixed Pedestal Mounts

The term “barbette” in railway artillery refers to mounts where the gun is fired in an open emplacement (not in a disappearing carriage or turret) – often high-angle fire – sometimes using a fixed or semi-fixed pedestal on the railcar. Many heavy railway guns, especially coastal types, essentially functioned as barbette guns on rails.

- Nations: United States (e.g. 16″ M1919), Great Britain (several 12″ and 18″ railway howitzers), Germany (some WWI guns placed on concrete “bettungsschiessgerüst” platforms), Soviet Union (later 305 mm TM-3-12).

- Design: his overlaps with other types. For example, the U.S. 16-inch M1919 barbette carriage was mounted on a railroad chassis – it had a huge base and the gun could elevate to +65°for long-range plunging fire. These typically did not have an armored turret, though they might have a shield. Often they required a firing foundation similar to Batignolles: e.g. the British 12″ railway gun Mk III had to be jacked onto a firing platform built of timbers and rails, essentially a fixed barbette base.

- Traverse: Ranged from limited (if firing from rails) to full circle (if placed on a central pivot or turntable). For instance, the U.S. 8-inch M1918 could traverse 360° on its pivot platform, effectively making it a barbette mount. The British 18-inch “Boche Buster” was fired from a static position with almost no traverse (aimed by track).

- Stabilization: Varied – some used ground platforms, others like the German “Bruno” series used elaborate concrete pits (a German 28 cm on Bettung could rotate on a central pivot similar to Batignolles).

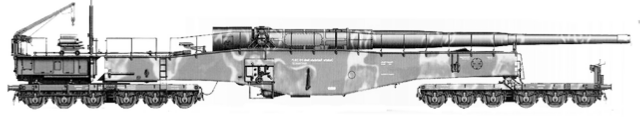

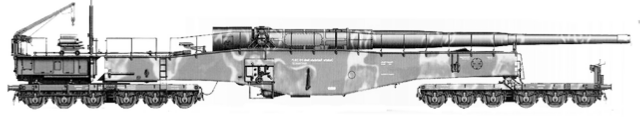

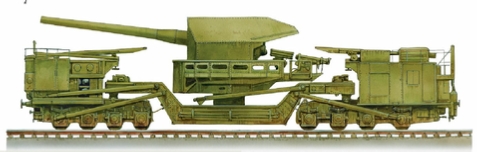

- Visual ID: Generally, no enclosing turret – the gun is exposed on an open framework or pedestal. Often very large caliber guns with gantry cranes for loading (since high-angle loading was an issue). Outriggers or jacks around the car are common. For example, the German 21 cm K12 and 28 cm K5(E) “Leopold” both had open mounts – the K5 sat on twin 12-wheel bogies with a fixed mounting allowing only 2° traverse (it had to be aimed on curved track, essentially a barbette on rails). The K5’s silhouette – a long gun on a flatcar with a minimal shield – is classic.

- Notable Examples: U.S.: 16-inch/50 M1919 guns (two built) on barbette carriages – these fired from prepared positions as seen in demonstrations. 8-inch M1888 guns on M1918 barbette railway carriages – ~47 of these were operational in WWII, often kept on standby near coasts. Britain: 12-inch Mk III railway gun, 12″ howitzers on wagon trucks, and the giant 18-inch Howitzer (Mark I “Boche Buster”) which was mounted on a huge railway carriage that lowered onto a fixed firing base (a barbette mount in effect). Germany: Schwerer Gustav 80 cm – though unique, this 1,350-ton gun was essentially a barbette on twin parallel railway tracks; it had to be assembled on-site and could traverse only on a special curved track segment. Also the K5(E) 28 cm guns mentioned – limited traverse (2°) meant they operated from prepared curved tracks or on a Vögele turntable when available

Pros and Cons

- Pros: Often the only way to mount extremely large guns – using a barbette approach allowed heavy shell and powder handling and high elevations for long range. They maximized range (e.g. the 16″ guns firing 2,340 lb shells ~28 miles).

- Cons: Many still needed extensive site prep, losing tactical mobility. Some had very limited traverse which complicated targeting (the K5 required frequent relocation on curved track to sweep across a target area). However, barbette mounts remained in service through WWII wherever massive firepower was needed from rail-mobile assets.

St. Chamond Mounting System (France, WWI)

Overview:

Developed by the French arms manufacturer Forges et Aciéries de la Marine et Homécourt (St. Chamond), this mounting system was an alternative to Schneider’s. It was used primarily for medium-caliber railway artillery.

Design Features:

- Used a hydro-spring recoil system, often mounted on a central pedestal.

- Allowed moderate traverse (up to ~10°) on the carriage without needing curved track.

- Featured elevated trunnion design, allowing higher elevation angles for plunging fire.

Visual ID:

- Recognizable by its often cylindrical, armored gun house with hatches and gunport slits.

- Carriages typically had six or eight axles and prominent jack-down supports.

Notable Use:

- Used with Canon de 194 mm modèle 1870/93 and other naval conversions.

- Supported French and American artillery units during WWI.

- Some St. Chamond carriages were imported by the U.S. and tested (although never widely adopted).

Kane-Peña Mounting System (Russia, WWI and Interwar)

Overview:

Originally a Russian adaptation of coastal artillery mounts, the Kane-Peña system was used on 12-inch and 14-inch guns mounted on railcars with fixed traverse.

Design Features:

- Combined a rigid pedestal mount with recoil absorption via inclined slide and hydraulic buffers.

- Typically featured zero on-mount traverse; full traverse was possible only via external rotating platforms or curved track.

- Intended for high-angle fire, often with howitzer-like ballistic trajectories.

Visual ID:

- Heavy-duty flatcar or girder carriages, with centralized mounting rings.

- Used raised loading platforms to enable breech access at high elevation.

- Distinctive slanted recoil path under the gun.

Notable Use:

- Deployed extensively by Imperial Russia and later the Soviet Red Army.

- Influenced later Soviet TM-1 and TM-3 rail artillery systems.

- Spain and Finland adopted or derived concepts from Kane-Peña in limited use.

Additional Mounting Systems

U.S. M1917 Railway Mount (4.7-inch Howitzer)

- First American-designed light railway mount.

- Used for 4.7-inch field howitzer, mounted on a simple flatbed with outriggers.

- Lightweight and intended for tactical use closer to the front.

- Rare, possibly only four produced; deployed to Panama Canal Zone.

- Visual: Short recoil slide, no gun house, wood-sided railcar.

U.S. M1919 Sliding Mount

- Based on French Glissement concept.

- U.S. test carriages built for 10-inch and 12-inch guns.

- Entire carriage rolled on firing and reset via winches.

- Visual: No recoil mechanism visible on gun, very flat platform.

Schneider 8" Chilean-Type Rotating Carriage

- Built for Chile but repurposed by U.S. after WWI.

- Had integrated turret ring on the carriage, allowing up to 360° traverse.

- U.S. built equivalent M1918MI rotating mount for 8-inch M1888 guns.

- Outriggers folded down to ground to provide stability when firing broadside.

- This type heavily influenced the M1A1 series for WWII.

German Bettungslafette (Bettung Platform Mount)

- Used for very heavy railway guns like the 28 cm K5(E).

- Gun was emplaced on a semi-permanent concrete platform with rotating ring.

- Not mobile during operation, but could be transported and emplaced.

- Visual: Static-looking base, very long guns, often with twin 12-axle bogies.

Summary Table of Mount Types |

|

Mount Type

|

Country

|

Traverse

|

Recoil Style

|

Key Features

|

|

Flatcar Pivot

|

USA/CSA

|

0–30°

|

None

|

Civil War era; simple, no recoil system

|

|

Glissement

|

France

|

0°

|

Carriage slides

|

Whole carriage recoils; simple but slow aiming

|

|

Schneider

|

France

|

~6°

|

Hydro recoil

|

Cradle with jacks; some traverse on mount

|

|

Batignolles

|

France

|

360° (on pivot)

|

Hydro + fixed base

|

Full traverse when emplaced on platform

|

|

St. Chamond

|

France

|

~10°

|

Hydro-spring

|

Self-contained recoil, armored shield

|

|

Kane-Peña

|

Russia

|

0° (car only)

|

Inclined slide

|

High-angle mounts, massive flatcar bases

|

|

U.S. M1917

|

USA

|

Limited

|

Hydro recoil

|

Lightweight tactical carriage, Panama only

|

|

M1918/M1A1 Rotating

|

USA

|

360°

|

Hydro recoil

|

Rotating carriage with outriggers

|

|

Bettungslafette

|

Germany

|

360°

|

Static mount

|

Installed on fixed platform, usually concrete

|

Summary of Key Differences

Each nation’s implementation had nuances, but these categories cover the major technical solutions. By WWII’s end, railway guns had grown impractically large and vulnerable (airpower made them easy targets), and thus these mount systems became a relic of a bygone era of siege warfare. The few surviving examples (like the Krupp K5 “Anzio Annie”) today serve as reminders of the immense engineering that went into these rolling giants.

- Recoil Handling: Sliding mounts let the whole carriage roll (simplest but least aiming ability). Top-carriage (Schneider) mounts had hydro-spring or hydro-pneumatic recoil absorbers, keeping the carriage mostly static. Platform (Batignolles) mounts combined internal recoil with transferring force to a ground platform (heavy prep but very stable).

- Traverse: Ranged from essentially none (sliding mounts) to a few degrees (most early carriages) to full 360° (pivoting mounts like Batignolles or Schneider rotating types). If full traverse was needed, either a central pivot platform or a built-in turntable was employed.

- Stabilization: Some mounts fired “off the rails” (Batignolles, barbette on platform) – requiring construction but sparing the track from abuse. Others fired “on rail” but clamped/jacked (Schneider, K5) – quicker to deploy but needing strong track and usually only low-angle fire unless a recoil pit was dug.

- Visual Identification: As a quick guide – Sliding mounts have no evident recoil cylinders and often an empty space behind for recoil travel. Schneider-type carriages show big recoil pistons and sometimes rail clamps; they look like standard railcars with a gun and perhaps folding supports. Batignolles-type have huge side girders, many wheels, and usually jacking mechanisms – often seen with their car body separated from the trucks in firing position. Chilean/Rotating mounts often have an armored look (partial turrets) and outriggers visible. Barbette mounts appear as very large guns on relatively simple flatcar bases, often with minimal shielding but heavy jacks around.