The first railway line in Bosnia and Herzegovina was opened for traffic on 24th December 1872. It was a standard-gauge track from Banja Luka to Dobrljina (101.6 km), built as a section of the Istanbul main route which was, in accordance with the Turkish plans, supposed to connect Istanbul and Vienna.

Following the Berlin Congress (1878), Austro-Hungarian Empire occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina and immediately began intensive construction of railways. The occupation troops built tracks along the routes of their penetration into Bosnia in order to ensure logistical supply of the military. As early as September 1878, construction of narrow gauge track was begun from Bosanski Brod to Sarajevo. On 10 September 1878, first Directorate of railways in Bosnia and Herzegovina was established, under the name “Directorate of k.u.k. Bosnian Railways“. Head of the Directorate was an Austro-Hungarian major – engineer Johan Tomašek.

Staff of the Directorate consisted of seven Austro-Hungarian officers and military officials, 30 civilian officials from Austria and Hungary and a number of other staff – all foreign. Local workers served as auxiliary staff. The military administration ordered that the section to Derventa must be completed in two months. Railway engines and available cars, owned by “Higel and Sagel“ company which was to build tracks in Bosnia, were transferred from Romania, where narrow-gauge track Timişoara-Oršava was being completed. These circumstances determined the future character of B&H railroads with narrow-gauge tracks of 0.76 m. Track to Derventa was built by 40 engineers and 4.000 workers, with several very difficult points along the route. There was no time for preparation of any technical studies and project analyses.

In the first phase, the degree of technical reliability of the constructed lines was on the lowest possible technical level and barely satisfied the minimum for safe operation of traffic. Radiuses of curves amounted to 30 meters; inclines were up to 16 per mill, while the superstructure was constructed from weak type VI rails of 13.5 kg/m of weight and 7 meters in length. A special problem lay in the switches, the so called “gypsies“, which blacksmiths made on the spot without rail-chair and with very weak links. The rolling stock consisted of small engines and cars. The engines had the strength of 20 to 40 horsepower, and open cars called “loris“ which carried up to two tons. Car coupling was simple and stiff connections caused trains to frequently break apart in curves.

Ten “loris” cars were modified for passenger traffic by posting vertical posts in four corners of the car and covering the top with cloth called “SEGEITUH“. Wooden boards were nailed on front and back of the car, while its sides were covered by curtains. All of these circumstances in the first days of the traffic resulted in enormously long traveling times, and the train from Bosanski Brod to Zenica took 15 hours to arrive. Corrections and improvement of the technical elements of the track took place in 1880. Construction of the line towards Sarajevo was continued. New engines of 50 horsepower were purchased along with new second and third class double-axled passenger cars and closed freight cars.

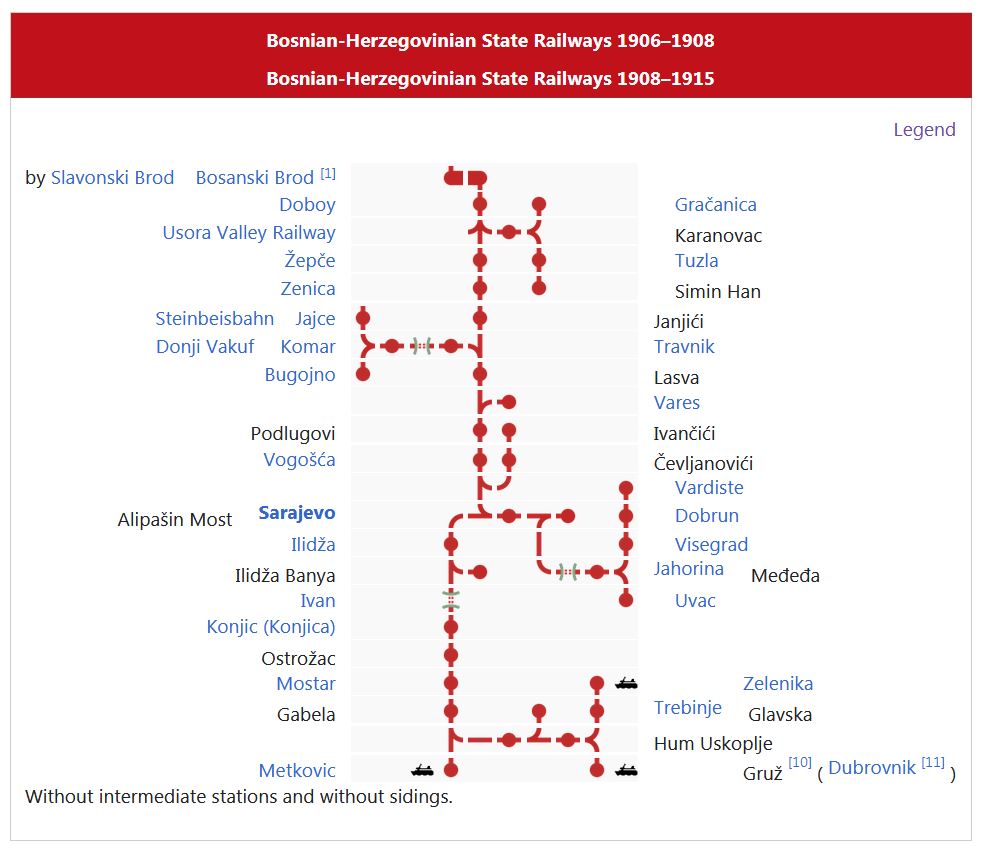

First section of this line from Bosanski Brod to Doboj was finished on 12th February 1879, from Doboj to Žepce on 22nd April 1879, and from Žepce to Zenica on 5th June 1879. The entire line was finished on 5th November 1882, when train engine “RAMA“ brought the first train into Sarajevo. The total length of this line was 270.117 km. In the course of further use, improvements were made on the track, the most significant of which was construction of Vranduk tunnel in 1910 and installation of type 4 rails of 22 kg of weight, which significantly improved the superstructure. The next constructed line was mining and forestry line Semizovac-Ivancici. Its main purpose was export of manganese ore from a rich deposit near Cevljanovici and freight of semi-processed logs.

The track was opened for traffic on 26th January 1885. With the desire to establish communication from the interior to the coast as quickly as possible, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy decided to construct the Southern line. The first section of this line, from Metkovic to Mostar, was opened for traffic on 14th June 1885. Construction of the Doboj-Šimin Han track (66.7 km), along the Valley of Spreca River, was completed on 26th April 1886 as a side connection on the primary main railway Doboj-Sarajevo. This line ensured export of high-quality coal and salt from the rich Tuzla basin.

In that same year, the Railway Directorate was moved from Derventa to Sarajevo. Because of low traffic capacity of the constructed railways, construction of the Southern line from Mostar towards Sarajevo was continued, and on 22nd August 1888 Mostar-Ostrožac section of the line was opened for traffic, while on 10th November 1889 the first train enters Konjic. Immense problems to constructors of this track were posed by Ivan saddle, a division line between the watersheds of the Black Sea and Adriatic Sea. It was necessary to arrive from the altitude of 876 m to a point at 279.1 m of height above sea level in Konjic over a very short distance. For that purpose a cogwheel mechanism, the work of Swiss engineer Roman Abt, was constructed. A 648 m long tunnel was dug through mountain Ivan. On the total route from Sarajevo to Konjic (55.8 km) a cogwheel mechanism covering 17.8 km in length was set. This section with the cogwheel mechanism had gradients of up to 60 per mill on the section of the track between Konjic and Bradina and 35 per mill on the section of the track between Pazaric and Bradina. Section of the railway from Konjic to Sarajevo was opened for traffic on 1st August 1891 which completed the connection with the Adriatic Sea. The problem of substantial grades on this route was partially solved on 9th April 1931, by digging of the Ivan tunnel of 3.223 m in length. The cogwheel mechanism from Raštelica towards Pazaric was removed and the track corrected in length of 6.7 km.

Austro-Hungarian engineers made projects for two more connections with the Adriatic Sea. One went along the constructed railway from Lašva to Travnik (26th October 1893) and from Travnik to Bugojno (14th October 1894.). It was envisaged that this line would go through Aržana to Split, but this connection was never constructed. The second connection to the Adriatic went from Donji Vakuf through Jajce. Construction of this line was finished on 1st May 1885.

Roman Abt’s cogwheel mechanism was also constructed on Travnik-Donji Vakuf track in order to deal with the watershed of Bosna and Vrbas rivers (Komar saddle) and a tunnel of 1.362 m in length was created. This connection via Bosanka Krajina region was accomplished with the construction of the military line Jajce-Srnetica in 1914, which connected onto the network of STAJNBAJSOVIHA tracks which went on to Knin. On 7 November 1895, Podlugovi-Vareš track of 24.5 km in length was completed and opened for traffic. It was used exclusively for exploitation of coal and iron ore at Breza and Vareš. Year 1895 is taken to mark the end of the first period of construction of BH railways. After three years of somewhat of a standstill, railroads Gabela-Zelenika, Uskoplje-Dubrovnik, and Hum-Trebinje of 179.6 km of total length were built purely as strategic and military, without any economic justification.

All three lines were opened for traffic at the same time on 16th and 17th June 1901. Likewise, for strategic reasons, the Monarchy decided to construct the Eastern line. The Eastern line was composed of two tracks: Sarajevo-Uvac and Međeđa-Vardište. The line is considered to be one of the most expensive, as its route was laid through very difficult rocky terrain and gorges. Ninety-nine tunnels and a great number of viaducts and supporting walls were built on that track. A kilometer of this line cost 450.000 golden crowns. The length of the Eastern line was 161.5 km, and it was opened for traffic on 4th July 1906.

During the occupation of Bosnia by the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, 547.8 km of privately owned forestry and mining lines were constructed in addition to the aforementioned lines. These served exclusively for exploitation of mineral and forest wealth. These were the lines owned by industrial businessman Otto Steinbas (later on Šipad’s lines): Prijedor-Knin, Srnetica-Jajce, Zavidovici-Han Pijesak-Kusace, and Usora-Pribnici.

A network of urban railways was constructed for the needs of the city of Sarajevo (5.271 km) and a side connection Ilidža-Ilidža Banja (1.28 km), all in the period from 5 January 1885 through 28th June 1891. In the interval between 1918 and 1942, the following lines were built in B&H: Bosanski Novi-Bosanska Krupa (4th October 1920) and Bosanska Krupa-Bihac (17th January 1924) with standard-gauge tracks. In the same period, narrow-gauge lines Bosanska Raca-Bijeljina, Bijeljina-Ugljevik, Trebinje-Bileca, Pazaric-Tarcin, and Metkovic-Ploce were constructed.

Unrealized expansion plans and takeover of the k.u.k. military railway

Around the turn of the century, the technical literature emphasized the cost advantages of the partly cogwheel-driven railways in Bosnian gauge and claimed that they were hardly inferior to standard-gauge railways in terms of their performance. In fact, the insufficient capacity of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian narrow-gauge railways became apparent as early as 1908 in the course of the annexation crisis and again in 1912/13 during the Balkan Wars .

In 1909, the General Staff of the Imperial and Royal Army drafted a military railway construction program that included the construction of the standard-gauge line Šamac–Sarajevo and the extension of the standard-gauge Imperial and Royal military railway Banjaluka–Dobrlin to Rama with a connection to the narrow-gauge Narenta Railway . Financial problems, limited opportunities on the Austro-Hungarian capital market and ongoing disputes in the state parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina prevented the realization of this or other expansion plans of the route network, such as e.g. B. the Sandschakbahn with the long-distance destination Thessaloniki. The switch toStandard gauge was reserved for the Yugoslav State Railways (JDŽ/JŽ) after World War II.

Because the Bosnian-Herzegovinian state government demanded that the Austro-Hungarian Military Railway Banjaluka-Dobrlin be handed over to the state, the standard-gauge military railway was ceded to the Bosnian-Herzegovinian State Railways on July 1, 1915 in a law of March 6, 1913.

First World War

Rapid rail transport was an important prerequisite for warfare with mass armies at the beginning of the 20th century. The aim of the operations against Serbia between August and December 1914 would have been a quick and decisive victory, but this was not achieved because of the limited capacity of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian narrow-gauge railways. The Austro-Hungarian troops suffered from a lack of food, warm clothing and ammunition. For the replenishment to the Serbian border, all transport goods had to be reloaded onto the narrow gauge in Bosanski Brod. A standard-gauge railway connection to the eastern and southern borders of Bosnia-Herzegovina would have been necessary for troop transport and supplies. Austria and Hungary thus became victims of their years of short-sighted railway policy.

The unsuccessful battles of 1914 had so exhausted the Serbian and the Imperial and Royal armies that there were no further battles for three quarters of a year and the BLBH were largely freed from military traffic. The 1916 campaign in the direction of Montenegro again led to major transport problems. Because of the crop failure in autumn 1915, food supply became one of the main tasks of the BHLB. The lack of operational traction vehicles was drastic. The many defective locomotives waiting for revisions led to traffic restrictions, and many machines were about to expire. Thanks to the uniform gauge of 760 mm, narrow-gauge locomotives from different parts of German- Austria couldto be contracted. In March 1916, after the conquest of Montenegro, military traffic declined and Henschel 's delivery of class VIc7 mallet wet-steam tug locomotives further eased the situation.

The increasing shortage of cogwheel locomotives was not solvable. The revision backlog due to a lack of personnel and material was two years and new cogwheel locomotives were not available. The harsh war years sapped the strength of the railroad workers, led to an increasing number of accidents and a drought in 1917 destroyed most of the crops. As in other parts of the monarchy, a systemic collapse was inevitable. The existence of the BHLB ended with the First World War.

Conclusion

Although the narrow-gauge network in Bosnia and Herzegovina is described as a major technical achievement in some railway publications, the effects are different from a historical perspective. Because there were no expansion measures around the turn of the century, the Bosnian-Herzegovinian narrow-gauge railways did not meet Austria's transport needs during the First World War nor those of the Yugoslav successor state.

Tack Route