The United States Railronistration (USRA) was the name of the nationalized railroad system of the United States between December 28, 1917, and March 1st, 1920. It was possibly the largest American experiment with nationalization, and was undertaken against a background of war emergency.

World War I began in Europe in July 1914. Long before the United States officially entered the war, it was involved as a supplier of materials to the Allied Powers. The movement of those materials to East Coast ports constituted a major traffic increase for the railroads after several slack years at the beginning of the Teens.

The United States entered the war on April 6, 1917. Five days later a group of railroad executives pledged their cooperation in the war effort and created the Railroad War Board. Among the problems the board had to deal with were labor difficulties, a patriotic rush of employees to join the Army, and a glut of supplies for the war effort choking East Coast yards and ports.

The efforts of the board were not enough for the government. On December 26, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson placed U. S. railroads under the jurisdiction of the United States Railroad Administration for the duration of the war. The director of the USRA was William G. McAdoo, Secretary of the Treasury and Wilson's son-

Two years of heavy traffic moving to Atlantic ports had left the Eastern railroads with roundhouses full of locomotives awaiting repairs. To alleviate the motive power shortage, the USRA proposed to design and purchase a fleet of standard locomotives.

The trade magazine Railway Age was initially cautious about the concept. Any design would be a compromise, too heavy for some rail-

As 1918 progressed, the tone of the editorials in Railway Age changed from cautious to hostile. The need for locomotives was immediate — did it make sense to design new ones rather than build to existing designs?' Would Standardization make any sense? The average locomotive run was about 150 miles, and there were approximately 2000 engine-

The USRA answered some of the arguments. Standardization would permit a tremendous Increase In locomotive production and would pro-

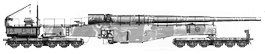

An engineering committee made up of representatives from the three principal locomotive builders (American. Baldwin, and Lima) and the railroads developed twelve standard locomotives in eight wheel arrangements: 0-

The USRA placed orders for 555 locomotives with Alco and 470 with Baldwin (Lima was already working at capacity). Originally the order was split by type, with only the light Mikado to be constructed by both builders, but the USRA soon changed the order so that both builders would construct all twelve types. Even the order for five heavy 4-

The reason for splitting the orders was to provide a foundation for future construction of the standardized locomotives. The initial duplication of work in creating patterns and jigs would be repaid in flexibility when orders could be placed with either builder for any of the types.

The initial allocations were published in June 1918. Among the roads receiving large batches were Baltimore & Ohio, 100 light Mikados; New York Central, 95 light Mikados; Milwaukee Road, 50 light Mikados Qater changed to heavy Mikados); Erie, 50 heavy Mikados (only 15 were delivered), 20 heavy Pacifies, and 25 heavy Santa Fes; Southern, 50 light Santa Fe’s. All five heavy Mountains, three from Alco and two from Baldwin, were for Chesapeake & Ohio.

The first order was placed on April 30, 1918, and on July 1, 1918, Baldwin outshopped Baltimore & Ohio light Mikado 4500. Railway Age reported the design was "straightforward throughout, with nothing of an unusual nature." The first heavy 2-

The first USRA 0-

The war ended in November 1918, perhaps sooner than the USRA anticipated. USRA control of the railroads continued until 1920, and the builders continued to produce USRA locomotives. In January 1919 Rail-

As the years passed, railroads modified their USRA locomotives. Pennsylvania Railroad 7961 has been rebuilt with a Belpaire boiler, and the smokebox front reflects standard Pennsy practice: small door, high headlight, and round number plate Otherwise the locomotive is still recognizable as a USRA heavy 2-

The USRA designs were good. The switchers were heavier and more powerful than contemporary 0-

Far more copies of USRA locomotives were built than originals — vindicating, perhaps, the arguments for standardization. Three decades later, alter another war, both the railroads and the locomotive builders suddenly embraced standardization — but the designs weren't Pacifies and Mikados but rather F7s, RS3s, and GP9s.

Background

Although the carriers had made massive investments in the first years of the 20th century, there remained inadequacies in terminals, trackage, and rolling stock. Inflation struck the American economy, and when in 1906 Congress empowered the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to set maximum shipping rates, the rail firms had difficulty securing revenue sufficient to keep pace with rising costs. The ICC did allow some increases in rates, however. Ownership of the 260,000-

European nations engaged in World War I ordered $3 billion of munitions from United States factories; and most of this production was routed through a few Atlantic port cities. Terminal facilities in these cities were not designed to handle the resulting volume of export tonnage, though German destruction of Allied cargo ships was ultimately a bigger problem. Thousands of loaded railroad cars were delayed awaiting transfer of their contents to ships; they were essentially used as warehouses. This resulted in a shortage of railroad cars to move normal freight traffic. The United States' declaration of war on April 6th, 1917, increased rail congestion by requiring movement of soldiers from induction points through training facilities to embarkation points.

The railroad unions (commonly called "brotherhoods"), desiring shorter working days and better pay, threatened strike action in the second half of 1916. To avert a strike, President Woodrow Wilson secured Congressional passage of the Adamson Act, which set the eight-

The railroads attempted to coordinate their efforts to support the war by creating the Railroads' War Board, but private action ran into anti-

Finally, in December 1917 the ICC recommended federal control of the railroad industry to ensure efficient operation. The takeover measures were to go beyond simply easing the congestion and expediting the flow of goods; they were to bring all parties—management, labor, investors, and shippers—together in a harmonious whole working on behalf of the national interest. President Wilson issued an order for nationalization on December 26, 1917. This action had been authorized by the Army Appropriations Act of 1916. Federal control extended over the steam and electric railroads with their owned or controlled systems of coastwise and inland water transportation, terminals, terminal companies, terminal associations, sleeping and parlor cars, private cars, private car lines, elevators, warehouses, and telephone and telegraph lines.

Changes and new equipment

The Light Mikado was the standard light freight locomotive and the most widely built type of the USRA standard designs.

Change happened swiftly. The railroads were organized into three divisions: East, West, and South. Uniform passenger ticketing was instituted, and competing services on different former railroads were cut back. Duplicate passenger services were reduced by eliminating more than 250 trains from eastern railroad schedules to allow increased numbers of freight trains to use crowded lines. Costly and employee-

Before the new USRA standard locomotive types were built and released, locomotives that builders had on hand were issued to various railroads. 2-

Progression

Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad employee's pass issued by USRA

On March 21, 1918, the Railway Administration Act became law, and Wilson's 1917 nationalization order was affirmed. Wilson appointed his son-

The law guaranteed the return of the railroads to their former owners within 21 months of a peace treaty, and guaranteed that their properties would be handed back in at least as good a condition as when they were taken over. It also guaranteed compensation for the use of their assets at the average operational income of the railroads in the three years previous to nationalization. The act laid down in concrete terms that the nationalization would be only a temporary measure; before, it was not defined as necessarily so. Both wages and rates for both passenger and freight traffic were raised by the USRA during 1918, wages being increased disproportionately for the lower-

With the Armistice in November 1918, McAdoo resigned from his post, leaving Walker Hines as the Director General.

Winding down

USRA ad from November 1919, promoting travel to California

There was support among labor unions for continuing the nationalization of the railroads after the war. However, this position was not supported by Wilson nor the public generally. Because the United States was not a party to the Treaty of Versailles ending the war in 1919, which would have been the legal basis for returning the railroads to private ownership under the Railway Administration Act, legislation was drafted to effect the return.

Congress passed the Esch-