Military Railroads in the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War - year 1870

The confusion on the ground was matched higher up the command chain. Because Niel’s idea of an overriding military commission in charge of the railways had failed to take root, orders for running trains came from everyone and everywhere ranging from the Ministry of War and its various bureaus to local authorities and préfects, right down to officers and non-

Orders would be countermanded and then reinstated with great frequency. The accumulation of wagons and matériel was legion and their use as storage was widespread, blocking up sidings and preventing their re-

The French strategy of invading Prussia before the enemy could mobilize was risky but, as Westwood suggests, ‘it might have won the war if only the French railways had been properly used’. However, they were not. Perhaps the French situation is best summed up by a despairing brigadier – who was in charge of 4,000 men – complaining that when he reached Belfort he had ‘not found my Brigade. Not found General of Division. What should I do? Don’t know where my regiments are.’ Many of the men, it turns out, were having much more fun. Behind the lines, a floating mass of supposedly lost soldiers had built up enjoying the hospitality of the jingoistic locals and making scant effort to find their regiments. The numbers involved were such that a group of up to 5,000 men had accumulated at Reims in eastern France, the capital of Champagne country, and had to be physically restrained from plundering the supplies in the wagons which had accumulated there.

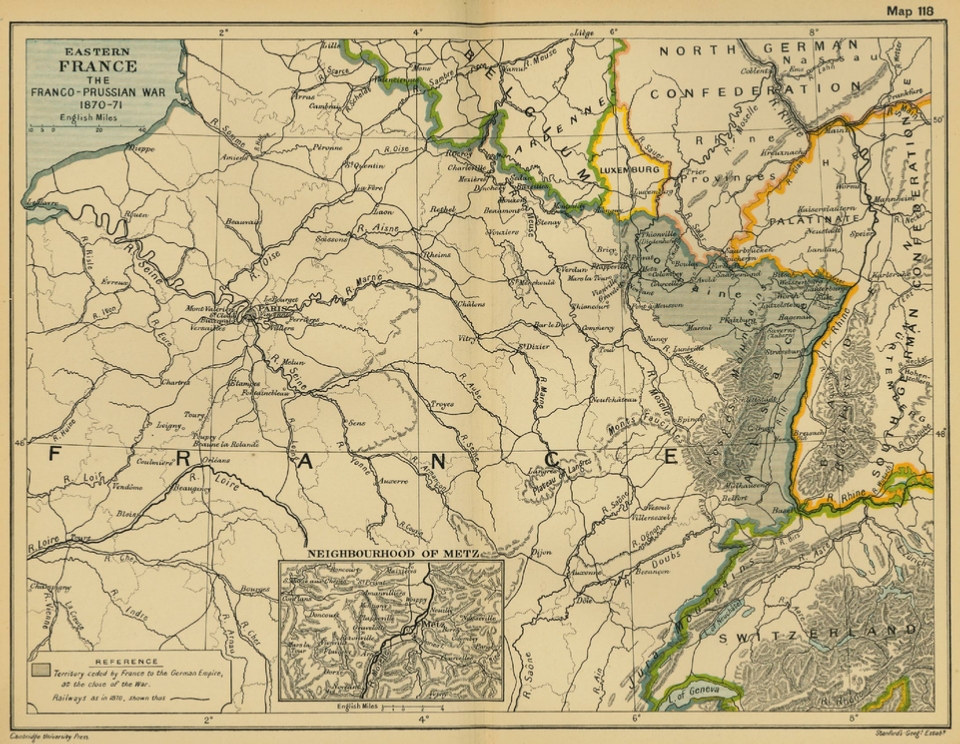

Metz, a few miles from the border, was the destination of much of this early traffic as it was initially the headquarters of the Army. Napoleon went there on 28 July to take control of the newly named Army of the Rhine which was already 200,000 strong and expected to expand as reinforcements arrived. After a series of defeats during August, Metz became besieged and supplies were limited, but the lack of organization on the railways made the situation far worse. Metz, in fact, had a large station with four miles of sidings and should easily have been equal to the task, but right from the start, with the arrival of the first infantry trains, there were delays in detraining owing to the absence of orders, and the supply wagons were mostly simply shunted into the sidings and effectively ‘lost’. According to Pratt, ‘everything was in inextricable confusion. Nobody knew where any particular commodity was to be found or, if they did, how to get the truck containing it from the consolidated mass of some thousands of vehicles.’ Consequently, when Metz eventually fell, the town was still awash with wagons, both full and empty, which the Germans were able to put to use. Pratt estimates that no fewer than 16,000 wagons were captured by the Germans at Metz and other parts of the French rail network, which, as he wrote, meant that ‘not only had the French failed to get from these 16,000 railway wagons the benefit they should have derived from their use but, in blocking their lines with them under such conditions that it was impossible to save them from capture, they conferred a material advantage on the enemy, providing him with supplies, and increasing his own means both of transport and of attack on themselves’.

The strategic importance of Metz led the Germans to draw up contingency plans, knowing that the town was a fortress and expecting, wrongly as it turned out, that the French would retain it well into the war. As a contingency, the Germans allocated 4,000 men to build a twenty-

This ‘Iron Cross Railway’, as it was dubbed by the locals, was an illustration of the thoroughness of the German planning. In contrast to the French, German mobilization had proceeded remarkably smoothly. Even though the Prussians did not, unlike the French, have a standing army, and therefore had to call up all its men, Moltke’s work over the previous four years bore fruit. As van Creveld suggests, ‘it was only necessary to push a button in order to set the whole gigantic machine in motion’. Crucially, Moltke insisted that the soldiers should be got to the front first, and their supplies would follow. The process was helped by the fact that thanks to the layout of the railways, and the work of the line commissions, six railway lines were available to the Prussian forces, and a further three to its allies in southern Germany. Moltke had reckoned they would reduce the time taken to move troops to the French border from twenty-

After that victory, the Prussians headed west to besiege Paris, though they hardly made use of the railways during this advance. The Germans had expected to fight the war on or around the border and had even prepared contingency plans to surrender much of the Rhineland, whereas in fact they found that, thanks to French incompetence, they were soon heading for the capital. The war, consequently, took place on French rather than German territory, much to the surprise of Moltke, upsetting his transportation plans, which had relied on using Prussia’s own railways. The distance between the front and the Prussian railheads soon became too great to allow for effective distribution, and supplies of food for both men and horses came from foraging and purchases of local produce. This was the result of a failure of planning and a lack of flexibility. The Prussians had expected to use railheads in their own country and did not have sufficiently well worked-

Efforts were made to advance the railheads but the Prussians found that many of the French railways had been rendered unusable thanks to the sabotage at which the French became remarkably adept. The most comprehensive damage was caused to the Nanteuil tunnel on the line between Reims and Paris, which was blown up with great precision by French military engineers who managed to bring down twenty-

This was the pattern throughout much of France. The French demolished large numbers of bridges and tunnels not only on the Est railway, whose area covered most of the battle sites, but also on the main lines of the Nord and, as the conflict spread to the west, the Ouest, the Paris-

At other times it was sheer incompetence that left the railways intact: ‘In one case, while engineers were inspecting a bridge prior to laying charges, the train which had brought them steamed off, taking their explosives with it.’ As in the US, the French discovered that simply removing track was ineffective, since the Prussians were not averse to shifting rails from the nearest branch line to replace those which had been removed. It could turn out to be a game of cat and mouse. After the French defeat near Wissembourg on 6 August, the last French train left the nearby railway center at Hagenau at 3 a.m., tearing the tracks up behind it to prevent pursuit, but by the morning of the next day, barely thirty hours afterwards, the first Prussian train arrived on newly relaid track to remove the wounded.

Indeed, instances of retreat always pose the most insuperable problems for the railway managers. Suddenly, hoped-

Another reason for the reduced role of the railway after the initial phase of the war was that the fortresses protecting the railways remained a formidable obstacle, despite Moltke’s recognition of this issue in his note to Bismarck after the Austrian war. In the early months of the conflict, several fortresses blocked the main lines towards Paris, preventing the Prussians from operating through-

The Prussians were hampered, too, by the activities of the francs-

In order to draw attention away from their own errors, the Prussians were wont to blame everything on the francs-

In fact, many of the derailments, minor accidents and track failures were due to the incompetence of the Prussian running of the railway rather than the result of attacks by partisans. Through the invasion, the Prussians gained control of 2,500 miles of French railway but operating it effectively was beyond them. They were, after all, working in a foreign country with strange equipment and with little help from French railway workers, who mostly abandoned their jobs once the Prussians arrived rather than collaborate with the enemy. In such conditions, accidents were inevitable but the francs-

A War of Mobilization

Those in France emanated, fan-

In France, where half a dozen large railway companies had emerged in the 1850s, the railways were privately operated but their construction was supported at times with substantial state investment. The routing of new lines was governed by commissions mixtes consisting of both public and private interests but there were several instances where the Army determined the route of a railway. However, military interests were by no means always paramount as three-

The same considerations were being assessed over the border in Prussia, by the same players. Military advisers wanted rail lines built under the protection of fortresses, at a safe distance from frontiers and on the ‘opposite’ side of waterways – in other words, the bank furthest from the likely enemy, whose identity was known to both sides long before the start of the war. Money, too, was often a deciding factor, though the military clearly won the argument over the construction of several lines, notably the Ostbahn, which could take troops to and from the north-

The Prussians, in fact, were at a disadvantage because they had a far greater number of railway companies, under different state administrations, and there was therefore far less uniformity in the system. The Minister of Railways in Saxony complained rather wittily that it would be ‘to the general good in peacetime, and of benefit to the military man in wartime, if the superintendent met at Cologne was dressed like the superintendent at Köninsberg, and if there was no danger of a Hamburg station inspector being taken for a superintendent of the line by somebody from Frankfurt’. Rather more alarmingly, he added that there were parts of the network on which a white light meant ‘stop’ and others where it signified ‘all clear’, a real risk to the safety of people traveling on the system.

In the run-

Meanwhile, in France, senior officers who were eager to stir up hostile opinion against Prussia were warning that the French railways were inadequate to the task of defending la Patrie and that the Prussians had the better system. In fact, neutral observers such as van Creveld, the logistics expert, suggest that the French system was better: ‘On practically every account, the French railway system in 1870 was actually better than the German one.’ Nevertheless, even though the anonymous Prussian officer was right, the difference in the two systems would not prove decisive because the French were ultimately let down by their administrative arrangements.

In the late 1860s, as war drew closer, both sides attempted to tailor their railways to the needs of the coming conflict. Moltke was, again, lucky. He had a counterpart in France, Maréchal Adolphe Niel, the Minister of War, whose ‘intentions were quite similar and his vision no less lucid’. Niel, like Moltke, attempted to reorganize the railways to ensure that in the event of war, they would be under central military planning. In this he was supported by his sovereign, Napoleon III, but his reforms stalled in the face of resistance from conservative elements within the government. However, before that opposition could be overcome, Niel died. It was to prove a most untimely death which left a series of half-

In Prussia, the whole approach to war was more scientific and thorough. Moltke had reorganized the Prussian general staff, taking on highly trained military personnel drawn from the cream of army officers. Nothing was left to chance. There was endless analysis and planning, with railway and logistical issues being accorded high priority, and the whole approach was completely unlike the military organization of any other European nation. Nowhere else was there this emphasis on a scientific approach to warfare. This resulted in a bizarre political structure with an army that held a place of almost feudal status in society being supported by a highly technocratic and effective machinery.

As part of this process, Moltke quietly introduced a key reform affecting the railways. The translation of the report written by McCallum on his experience of running the railways for the North in the American Civil War was influential in convincing the Prussians that they must adopt the same structure. On this basis, Moltke was able to push through a reform enabling the military to strengthen its control over the railways, in particular those running on an east-

The line commissions remained inactive until the outbreak of war, when their first task was to issue emergency schedules to the key stations along the line. These schedules, which had been prepared in advance, were far more detailed and sophisticated than a simple timetable, setting out precisely the composition of each train, the number of men to be moved and even refreshment stops: ‘The execution of these schedules was to be so precise that many trains would be able to make connections en route, dropping and attaching cars to ensure that units would be complete, in their order of battle, when their trains arrived at the concentration areas.’

The war was actually declared by the French, the culmination of years of tension between the two sides over a variety of issues. The actual casus belli was obscure in the extreme, the candidacy of Leopold, a prince belonging to the Hohenzollern family, the rulers of Prussia, for the throne of Spain, which had been rendered vacant by the Spanish revolution of 1868. Under pressure from Napoleon III, who did not want France to be encircled by a Spanish-

Napoleon’s cause was imperiled right from the outset by the chaotic mobilization of the troops on the French side. It was not the fault of the railway companies. Already, four days before the official outbreak of war, the five big main-

This was a portent of things to come. Sure, nearly a thousand trains were dispatched from Paris over the next three weeks, carrying 300,000 men and 65,000 horses, as well as countless guns, ammunition and supplies. Moreover, the French got to the frontier first. After a mere ten days, 86,000 men had reached the border, while hardly any Prussian soldiers were there to face them on the other side of the Rhine. However, the bare statistics mask an incompetent and ill-